Lachlan River & Wetlands

The Lachlan Catchment

The Lachlan Catchment is one of 22 catchments grouped as the Murray–Darling Basin (MDB). The MDB is also described as one interconnected system of rivers across those 22 different catchments. Yet the Lachlan differs in that it is the only regulated MDB river system considered to be essentially ‘disconnected’ from either the Darling or the Murray. While technically a tributary of the Murrumbidgee River (Outhet, 2011), the Lachlan River now generally only connects to the Murrumbidgee River and the MDB when both the Lachlan and Murrumbidgee Rivers are in flood. The catchment is unique in the Murray Darling Basin in the extent and manner it terminates in wetlands and diverging creeks.

What is ‘unique or special’ about the Lachlan?

One of the most common information requests the Portal Team receive is:

“Where can I find a snapshot of the Lachlan that highlights unique or exceptional features?’

Below is a start. Much more can be found within the rest of the Lachlan Environmental Water Management Portal (LEWMP).

There are significant and diverse wetland types all along the Lachlan River basin. Such as Lake Cowal within a large flood plain, the Jemalong Plain. Lake Cowal is the largest natural inland lake in New South Wales and part of the Wilbertroy–Cowal Wetlands complex, listed in the Directory of Important Wetlands in Australia (DIWA). Lake Cargelligo and Lake Brewster are others.

-

-

- The Lachlan River ‘terminates’ in a low-gradient, low energy drainage basin called the Great Cumbung Swamp. The wetlands of the Great Cumbung Swamp, are extensive and unique.

- Lake Brewster has some of the largest and most regular Australian Pelican breeding colonies in the regulated MDB. It is the only remaining pelican breeding ground in the Lachlan, and also supports significant waterbird diversity and abundance.

- The Brewster Weir pool is home to one of the rarest native fish species in the MDB, the Olive Perchlet (western population) (Ambassis agassizii). The population was rediscovered in 2007 in the Lachlan and regular monitoring as recent as summer 2022 has confirmed that the population is breeding and self-sustaining.

- Similarly, the Lachlan has two populations of the Hanley’s River freshwater snail, which was once common and widespread in the Murray River catchment including the Lachlan and Murrumbidgee Rivers. They are now virtually extinct throughout their natural range.

- The Lachlan sustains colonial waterbird breeding populations. The Merrimajeel (Booligal) rookeries are notable on their own – with over 100,000 ibis (mainly straw-necked ibis) nests alone in 2016–17, 65,000–125,000 nests in 2010–11, and 9 colonies between 10,000 and 80,000 nests since 1984. Lake Cowal also contributes colonies in the 10,000 to 20,000 nests when flooded although it is less studied.

- The Lachlan is spatially extremely variable which maintains a diverse assemblage of wetland habitats. The catchment has some of the driest and wettest sites of all sites monitored across the Basin. The Lachlan has had the greatest number of plant species recorded of all the selected areas across the Basin (2014 2020) in the Commonwealth’s Flow MER program. A total of 359 plant species recorded in the Lachlan. This is greater than the 321 in the Gwydir, 303 in the Warrego Darling, 246 in the Bidgee, 63 in the Edward/ Kolety , and 150 in the Goulburn [Pers. Comm. Higgisson Basin Flow MER Program Vegetation Theme ( https://flow mer.org.au/basin theme vegetation/].

- The Lachlan is essentially one of the longest rivers in Australia after the Murray (approx. 2,500 km), at almost on par with Murrumbidgee and Darling (all around 1,400 km) and of the twenty-three major rivers in the Murray–Darling Basin (Geoscience Australia, 2012).

- A significant proportion of total catchment area is wetlands (471,011 ha or 5.6% of the total catchment area), and greater proportion that greater than the Murrumbidgee, Darling, Murray, and Gwydir Catchments (those with greater proportion are mainly the unregulated in northern MDB).

-

The Lachlan River

The Lachlan is almost a tale of two river catchments. The landscape of the Lachlan Catchment varies markedly from east to west as it moves from the headwaters and tablelands, through the slopes of the middle catchment, to the flat, western plains of the Lower Lachlan.

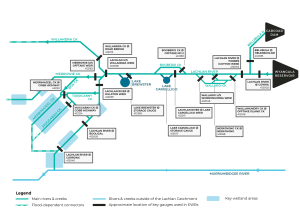

The Lachlan Long Term Water Plan (LTWP) includes the below Schematic Diagram of the Lachlan system which illustrates the progression from tributaries, anabranches and distributaries in a downstream direction.

The named Lachlan River starts in the east as a chain-of-ponds in a drained lake basin near the village of Breadalbane, between Yass and Goulburn. The eastern catchment boundary forms part of the Great Divide, which extends along the entire eastern side of Australia. Most of the runoff and sediment is derived from its small highland (tableland) catchment, roughly one-fifth of its total area, approximately 18,700 km2 Four major tributaries rise from this area, namely the Abercrombie, Belubula (Figure 1) and Boorowa Rivers, and Mandagery Creek. A tributary is a stream or river that flows towards or into the mainstem, contributing to the total flow in the main river it joins. After leaving the highlands, the Lachlan has no permanent tributaries. It has a number of anabranches characteristic of the mid-Lachlan area, such as Booberoi and Wallaroi creeks (Figure 1). An anabranch is a stream that leaves a river and re-enters it further along its course.

The channel contracts with distance downstream of Forbes until, at Hillston, its capacity is only 16% that at Cowra (Kemp, 2001). Apart from the Torriganny Creek, the Lower Lachlan below Lake Brewster is dominated by distributary creeks. A distributary is a stream that branches off and flows away from a main stream channel. Distributaries are a common feature of river deltas.

The Lachlan River contracts with distance downstream of Forbes until, at Hillston, its capacity is only 16% that at Cowra (Kemp, 2001). This decrease in discharge downstream with associated reductions in channel size are typical of the lower reaches of dryland rivers subject to variable floods and have significant transmission losses, distributary outflows and few tributary contributions in their lower catchments (Tooth, 1999, 2000). In the Lachlan, it is particularly pronounced below Lake Brewster, providing for a unique and diverse typology of floodplain wetlands, floodouts, and braided channel systems not only associated with the Lachlan River channel, but an extensive alluvial fan that includes for example, Willandra, Middle, Merrowie, Box, Merrimajeel, and Muggabah creeks (Figure 1).

Overview of Lachlan Catchment Wetlands

In a state-wide mapping project involving 17 catchments, the total area of wetlands in the Lachlan was estimated at 471,011 ha or 5.6% of the total catchment area (compared to the state average of 6.5% or a total wetland area of 66,580,826 ha; Kingsford et al., 2003). The Lachlan Catchment ranked seventh in terms of the proportion of total catchment area which was comprised of wetlands, with a value similar to the Darling and Lower Murray (NSW portion only) catchments. The 12 catchments (including the Lachlan) with 6% or less of wetland area in their catchment included most of the major regulated rivers in NSW. A table summarising the state-wide mapping project (Kingsford et al., 2003) with reference to the relative ranking of the Lachlan Catchment can be viewed in Table 1 below.

Note: Lake Brewster and Lake Cargelligo have not been included in this table due to the complexities of water use and management required for these two wetlands.

| Wetland | Guage no. | Gauge height (m) | Discharge (ML/d) | Date; Duation of last inundation | Volume required (ML) | Condition | Delivery constraints |

| Cumbung: Reed Bed | 412005 | 0.5–0.67; 1.1 for significant response | 275–661; 713 for significant response | 2010/11; >6 months | 5000 to 30 000 | Poor | Levees |

| Cumbung: Lignum Lake | 412005 | 1.1 | 713 | 2010/11 | 25 000 to 30 000 | Unknown | |

| Cumbung: Marrool Lake | 412005 | 1.1 | 713 | 2010/11 | 25 000 to 30 000 | Unknown | |

| Lake Cowal | 412036 | 7.2 | 14 500 | 2010/11 | Moderate–good | Large volumes required; delivery difficult | |

| Booligal Wetlands | 412005 | 2.1 (BB); 0.47(CTF) | 2500 (BB); 236 (CTF) | 2010/11; ~6 months | 12 000 to 57 000 | Moderate–good | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient |

| Lake Merrimajeel | 412005 | 1570 | 2010/11; >6 months | 500 | Moderate | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient | |

| Murrumbidgil Swamp | 412005 | 1560 | 2010/11; >6 months | 3500 | Poor–moderate | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient | |

| Cuba Dam | 412039 | 1.07 | 1500 (with Gonowlia Weir open) | 2010/11; >6 months | 4000 | Moderate | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient |

| Merrowie Creek (Cuba Dam to Chillichil) | 412039 | 1.07 (3.1 required at Willandra Weir) | 1500 (with Gonowlia Weir open) | 2010/11; >6 months | 6000 | Moderate | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient |

| Lachlan Swamp | 412005 | 850 | 2010 | up to 20 000 | Moderate | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient |

Guage no. and name: 412005=Booligal Weir, 412036=Jemalong Weir, 412039=Hillston Weir

CTF=Commence-to-flow; BB=Block Bank

In the Lachlan Catchment, of the three spatially derived wetland groups (and reservoirs) for inland wetlands, 95% are floodplain wetlands and 5% freshwater lakes, with no saline lakes mapped (Kingsford et al., 2003). The dominance of the floodplain wetland group was common across NSW, with over 70% of wetland area classified as floodplain for all but two of the 17 catchments, with an average of 93% floodplain across the state. Reservoirs, which reflect the level of river regulation and development to some extent, were also mapped and included open bodies of water usually created by a wall or levee, such as reservoirs, farm dams, off-river storages, mining and quarry dams, sewage ponds, evaporation ponds, evaporation basins, canals and open basins (Kingsford et al. 2003). The Lachlan Catchment was ranked as containing the fourth greatest total number of reservoirs at 163 structures.

Lachlan Environmental Water Management Portal and Lachlan Catchment Wetlands

One objective of the LEWMP is to set priorities for environmental watering. To assist in this process a number of wetlands have been recognised at national and regional levels as containing ecological, cultural or social values. These wetlands are included included as priority water-dependent features in the Lachlan Long Term Water Plan (LTWP). The foundation of the LEWMP is the Lachlan LTWP which guide the management of water for the environment over the longer term and at a catchment scale, and complement the Basin-wide environmental watering strategy. The plans inform the work done to deliver water for the environment.

This website contains specific sections accessed via the internal hyperlinks on the eight Nationally Significant Wetlands and nine Regionally Significant Wetlands, and other important in-channel water-dependent assets and priority locations (Riverine Key Features and Priorities) within the Lachlan Catchment.