Environmental Watering Planning Framework

Background of Reform

Australia has been reforming how water is used and managed for over thirty years. The journey continues at both the State and Commonwealth level in 2022.The NSW RiverBank (2005 to 2011) was a landmark program. It was the first Australian government program to purchase water for the conservation of rivers and wetlands. Purchased licences are now held by the Minister for the Environment as adaptive environmental water licences. Their use for environmental purposes is outlined in Water Use Plans. Funding from the Commonwealth Government’s Water Smart Australia fund was granted to extend RiverBank investment under the NSW Rivers Environmental Restoration Program (RERP). By end of January 2011, RERP and RiverBank had purchased 24,103 megalitres (ML) of general security and 1,000 ML of high security water access entitlements in the Lachlan. In addition, the Lake Brewster Water Efficiency Project provided for 12,000 ML of general security in June 2009. A further 795 ML of high security was recovered in September 2012 from the Pipeline NSW Program (Noonamah Water Authority).

RiverBank was a notable step in the reform of water management in NSW which had been progressing for over a decade. Extensive consultation in the late 1990s led to the Water Management Act 2000 (WM Act), replacing the Water Act 1912. Similarly, the WM Act 2000 was the first legislation in Australia to specify the right of the environment to a share of the available water resources as a priority. Water sharing plans are a statutory obligation under the Water Management Act 2000, and the primary instrument for implementing these reforms at a catchment-scale. The Water Sharing Plan for the Lachlan Regulated River Water Source 2003 commenced on 1 July 2004, and was one of the first such plans in NSW.

The Riverbank Water Use Plan for the Lachlan Water Management Area was made under section 8E(7) of the Water Management Act 2000. The specific areas prioritised by RiverBank for water delivery are worth noting. This water use plan guided the early use of environmental water holdings in the Lachlan. Those priorities remain and now incorporated into the Lachlan Long Term Water Plan.

At a Commonwealth level, the Australian Government (and the states) began the current major reform process starting with the Water Act 2007, culminating in the 2012 Murray–Darling Basin Plan (MDBP or Basin Plan hereafter). The Water Act 2007 created a single federal agency, the Murray–Darling Basin Authority to implement and review the performance of the Basin Plan. As part of this process, the Commonwealth Government purchased additional water entitlement (general and high security) for the environment in the Lachlan between 2008 and 2010. As a result, the Commonwealth currently holds 87,000 megalitres (ML) of General Security (GS) and 933 ML of High Security (HS) in the Lachlan. The holdings are managed by the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (CEWO) in partnership with the NSW Department of Planning and Environment (DPE). This is so that all licensed water for the environment is essentially managed collectively and delivered as joint watering actions wherever possible.

Annual and Long TermWater Plans and Priorities

Heading

Given the States held and managed environmental water before the Commonwealth, NSW already held the necessary water licences and works approvals, and supporting governance arrangements. To avoid duplicate, the NSW Department of Planning and Environment is responsible for the delivery of all water for the environment in NSW. This includes water held by the Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. A Partnership Agreement (Agreement) was established for coordinating environmental watering undertaken by DPE EHG and CEWO, including an agreed process for planning and managing the transfer, delivery and monitoring of Commonwealth environmental water in NSW.

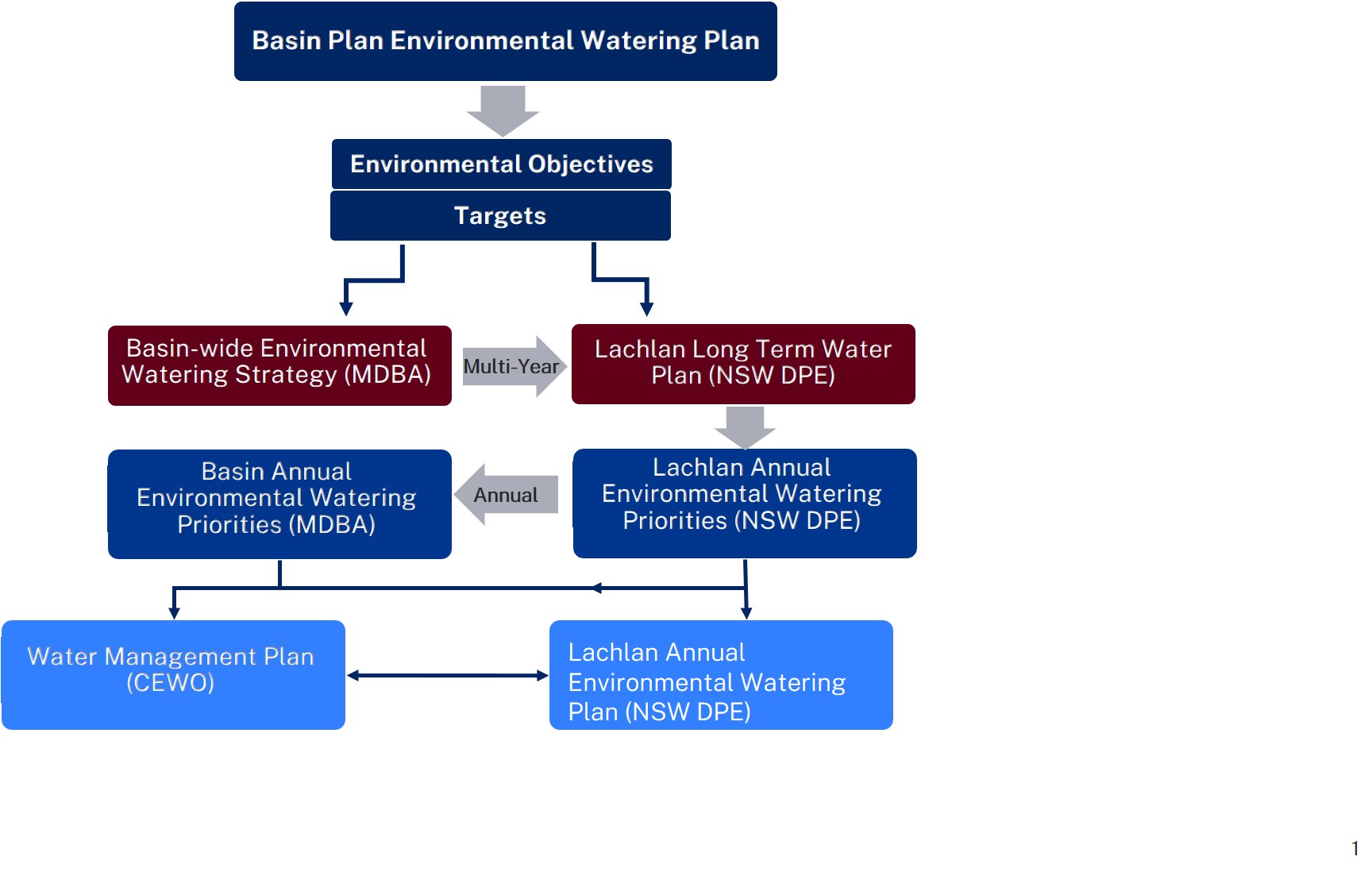

The Basin Plan 2012 (the Basin Plan) was made a legislative instrument on 22 November 2012. The Basin Plan includes an environmental watering plan that provides a overarching framework for planning and coordinating environmental water management (Figure 1 below). It establishes a common set of objectives, principles, and priorities for environmental watering.

The Basin Plan set out three broad environmental objectives that underpins the environmental water planning framework. These are to:

Water-dependent features or ecosystems is a broad term. It includes landscape or physical features such as rivers and wetlands, and the surrounding water-dependent vegetation or habitats. Ecosystem functions are the resources and services that sustain human, plant and animal communities, and are provided by the processes and interactions that occur within and between ecosystems. For example, improving hydrological connectivity along river systems, and between rivers and their riparian corridors and floodplain. This moves nutrients, carbon and sediments, enhancing productivity, and allows organisms to disperse, and improves water quality.

The objectives across the five themes cover key life cycle requirements, across all climatic and water arability conditions from Very Dry to Very Wet. The focus is often to maintain and avoid critical loss during drier conditions, to improve condition, restore ecological functions, and increase extent or abundance under wetter conditions.

Frogs and Frog Habitat

A number of threatened and/or endangered frog species have been listed for the Lachlan Catchment. This includes the Yellow-spotted Bell Frog (Litoria castenea), a critically endangered species under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act (1995), and endangered under the Commonwealth Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999), which has recently been discovered in the Southern Tablelands of the upper Lachlan Catchment. Recovery plans have been put in place for this species. Another threatened species, the Southern Bell Frog (Litoria raniformis), has not been recorded in the catchment over recent years (Wassens 2005). This frog species is associated with many wetland types, preferring slow flowing natural water bodies containing emergent aquatic vegetation (Office of Environment and Heritage).

Yarnel Lagoon and Burrawang West Lagoon are known to support breeding populations of a number of frog species including the Barking Marsh Frog (Limnodynastes fletcheri), Peron’s Tree Frog (Litoria peronii), the Inland Banjo Frog (Lymnodynastes interioris) and the Desert Tree Frog (Litoria rubella) (Wassens et al. 2007, Wassens and Maher 2010). The delivery of appropriate flows to these wetlands is essential to maintaining these important frog populations.

More recent information on the occurrence of frog species found the distribution of Littlejohn’s Tree Frog (Litoria littlejohni), listed as vulnerable (EPBC and NSW TSC), included the upper Lachlan. However, there is little information on how flows might be better managed to ensure frog survival. Information on the abundance, species composition, richness and diversity of frog communities is needed, as well as information about the factors that influence populations, such as time since last flood, inundation frequency, habitat structure, and water quality.

The Lachlan River

The Lachlan is almost a tale of two river catchments. The landscape of the Lachlan Catchment varies markedly from east to west as it moves from the headwaters and tablelands, through the slopes of the middle catchment, to the flat, western plains of the Lower Lachlan.

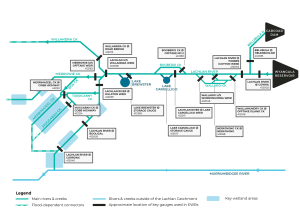

The Lachlan Long Term Water Plan (LTWP) includes the below Schematic Diagram of the Lachlan system which illustrates the progression from tributaries, anabranches and distributaries in a downstream direction.

The named Lachlan River starts in the east as a chain-of-ponds in a drained lake basin near the village of Breadalbane, between Yass and Goulburn. The eastern catchment boundary forms part of the Great Divide, which extends along the entire eastern side of Australia. Most of the runoff and sediment is derived from its small highland (tableland) catchment, roughly one-fifth of its total area, approximately 18,700 km2 Four major tributaries rise from this area, namely the Abercrombie, Belubula (Figure 1) and Boorowa Rivers, and Mandagery Creek. A tributary is a stream or river that flows towards or into the mainstem, contributing to the total flow in the main river it joins. After leaving the highlands, the Lachlan has no permanent tributaries. It has a number of anabranches characteristic of the mid-Lachlan area, such as Booberoi and Wallaroi creeks (Figure 1). An anabranch is a stream that leaves a river and re-enters it further along its course.

The channel contracts with distance downstream of Forbes until, at Hillston, its capacity is only 16% that at Cowra (Kemp, 2001). Apart from the Torriganny Creek, the Lower Lachlan below Lake Brewster is dominated by distributary creeks. A distributary is a stream that branches off and flows away from a main stream channel. Distributaries are a common feature of river deltas.

The Lachlan River contracts with distance downstream of Forbes until, at Hillston, its capacity is only 16% that at Cowra (Kemp, 2001). This decrease in discharge downstream with associated reductions in channel size are typical of the lower reaches of dryland rivers subject to variable floods and have significant transmission losses, distributary outflows and few tributary contributions in their lower catchments (Tooth, 1999, 2000). In the Lachlan, it is particularly pronounced below Lake Brewster, providing for a unique and diverse typology of floodplain wetlands, floodouts, and braided channel systems not only associated with the Lachlan River channel, but an extensive alluvial fan that includes for example, Willandra, Middle, Merrowie, Box, Merrimajeel, and Muggabah creeks (Figure 1).

Heading

The watering requirements and watering history of the nationally and regionally significant wetlands are summarised below. This summary helps the decision-making process by matching available environmental water with the requirements of each wetland and time since last appropriate watering.

Note: Lake Brewster and Lake Cargelligo have not been included in this table due to the complexities of water use and management required for these two wetlands.

| Wetland | Guage no. | Gauge height (m) | Discharge (ML/d) | Date; Duation of last inundation | Volume required (ML) | Condition | Delivery constraints |

| Cumbung: Reed Bed | 412005 | 0.5–0.67; 1.1 for significant response | 275–661; 713 for significant response | 2010/11; >6 months | 5000 to 30 000 | Poor | Levees |

| Cumbung: Lignum Lake | 412005 | 1.1 | 713 | 2010/11 | 25 000 to 30 000 | Unknown | |

| Cumbung: Marrool Lake | 412005 | 1.1 | 713 | 2010/11 | 25 000 to 30 000 | Unknown | |

| Lake Cowal | 412036 | 7.2 | 14 500 | 2010/11 | Moderate–good | Large volumes required; delivery difficult | |

| Booligal Wetlands | 412005 | 2.1 (BB); 0.47(CTF) | 2500 (BB); 236 (CTF) | 2010/11; ~6 months | 12 000 to 57 000 | Moderate–good | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient |

| Lake Merrimajeel | 412005 | 1570 | 2010/11; >6 months | 500 | Moderate | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient | |

| Murrumbidgil Swamp | 412005 | 1560 | 2010/11; >6 months | 3500 | Poor–moderate | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient | |

| Cuba Dam | 412039 | 1.07 | 1500 (with Gonowlia Weir open) | 2010/11; >6 months | 4000 | Moderate | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient |

| Merrowie Creek (Cuba Dam to Chillichil) | 412039 | 1.07 (3.1 required at Willandra Weir) | 1500 (with Gonowlia Weir open) | 2010/11; >6 months | 6000 | Moderate | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient |

| Lachlan Swamp | 412005 | 850 | 2010 | up to 20 000 | Moderate | Delivery between Dec–March inefficient |

Guage no. and name: 412005=Booligal Weir, 412036=Jemalong Weir, 412039=Hillston Weir

CTF=Commence-to-flow; BB=Block Bank

this is a paragraph